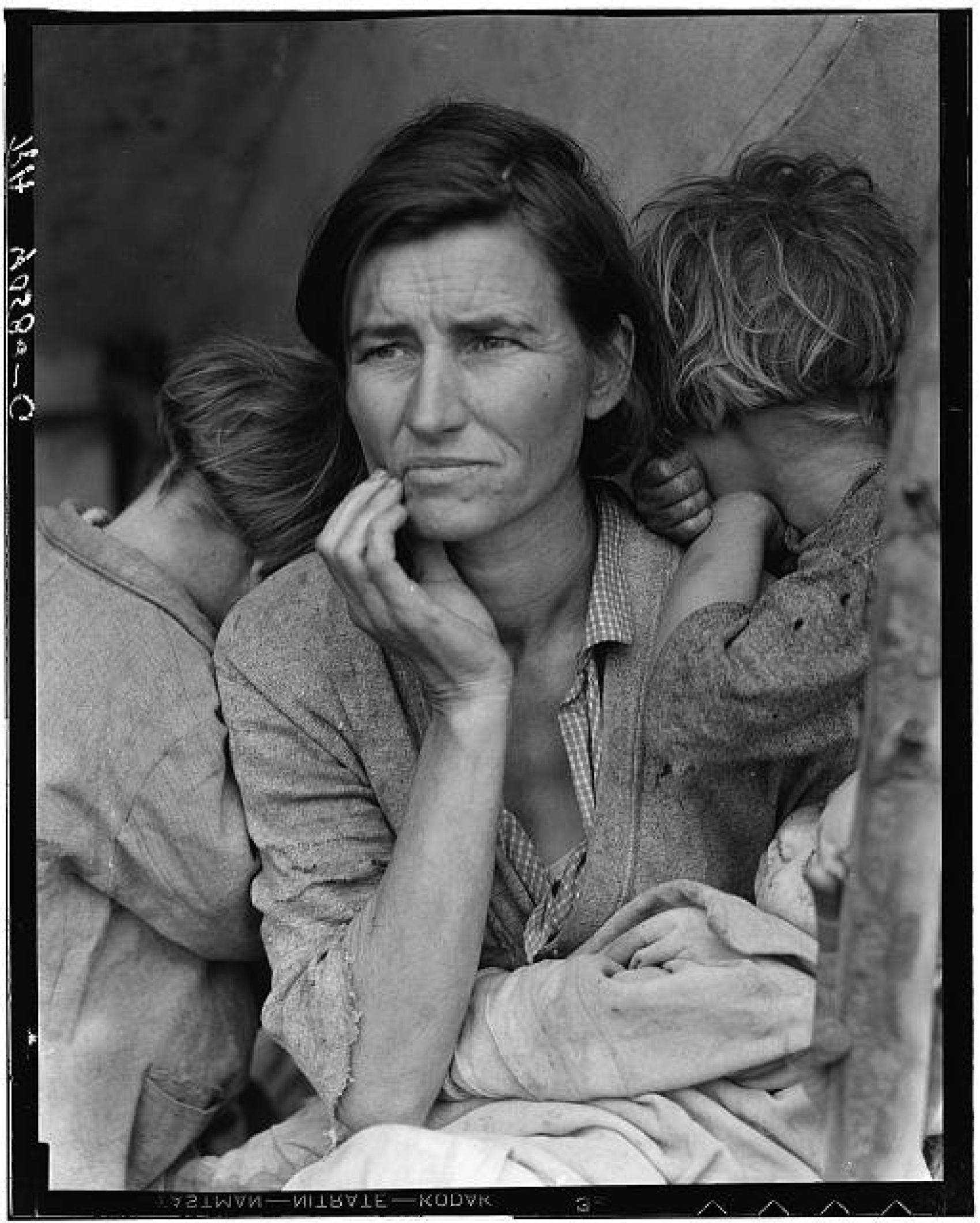

I was asked last year to select one photograph that has profoundly influenced my life. I chose an image known as Migrant Mother— a haunting picture of a woman named Florence Owens Thompson sitting with three of her children in their makeshift home, a rudimentary tent. The photograph was taken in California in 1936 as millions of American families struggled through the Great Depression. Florence and her family are destitute and desperate.

That iconic photograph, which I first came across in high school, still comes to mind whenever poverty is the topic of conversation. Poverty as a category of analysis is an abstraction. Migrant Mother captures its harsh, biting reality better than any other image— and any dictionary definition or economic indicator— that I have ever seen. And what motivates me is that, 70 years on, this struggle is still daily life for more than a billion people around the world.

In my work I have seen that struggle firsthand. I have seen how lack of family planning advice and contraceptives leaves parents with more mouths to feed than they can afford; how not getting the right food and nutrients leaves people unable to fulfil their potential; and how disease leaves adults too weak to work, and children too sick for school.

So while there are robust and legitimate debates going on about the methodology and measurements we use to classify poverty, first and foremost we must remember what it actually means to be poor. Essentially, being poor is about deprivation. Poverty not only deprives people of food, shelter, sanitation, health, income, assets and education, it also deprives them of their fundamental rights, social protections and basic dignity. Poverty also looks different in different places. While in East Africa it is related mostly to living standards, in West Africa child mortality and lack of education are the biggest contributors.

All this complexity and variation is impossible to capture in a definition of poverty as simplistic as living on less than $1.90 a day. If we really mean to “end poverty in all its forms everywhere,” as laid out in the first Sustainable Development Goal (SDG), then it fits that we have to know what all those forms are. We need to have a far clearer picture of the most marginalized and most vulnerable. Not just those who are financially poor, but those facing a number of distinct disadvantages, such as gender, race and ethnicity, that taken together deprive them of the chance to lead healthy, productive lives

One of the reasons I find Migrant Mother so powerful is that it focuses on the plight of a woman and how she is scarred by deprivation, at a time when their hardship and suffering was sometimes overlooked by politicians and policymakers. It is critical to know more about the lives of today’s Florence Owens Thompsons since women and girls are widely recognized as one of the most disregarded and disenfranchised groups in many developing countries. Indeed, the World Bank argues that a “complete demographic poverty profile should also include a gender dimension,” given that most average income measurements miss the contribution and consumption of women and girls within households entirely.

For a long time, for example, when data collectors in Uganda conducted labour force surveys, they only asked about a household’s primary earner. In most cases, the main breadwinner in Ugandan households was the man, so the data made it look like barely any women were participating in the workforce. When the data collectors started asking a second question— who else in the household works?— Uganda’s workforce immediately increased by 700,000 people, most of them women. Obviously, these women had existed all along. But until their presence was counted and included in official reports, these women and the daily challenges they faced were ignored by policymakers. Similarly, because many surveys tend to focus solely on the head of household— and assume that to be the man— We have less idea of the numbers of women and children living in poverty and the proportion of woman-headed households in poverty.

Getting a clearer picture of poverty and deprivation is a fundamental first step towards designing and implementing more effective policies and interventions, as well as better targeting scarce resources where they will have the greatest impact. That’s why our foundation is supporting partners to better identify who and where the poorest and most vulnerable are, collect better information on what they want and need to improve their lives and develop a better understanding of the structural barriers they face. The findings will then be used to develop strategies that specifically target those identified within the first 1,000 days of SDG implementation.

This report is a welcome contribution to these efforts, along with the United Nations Development Programme’s ongoing work to revamp the Human Development Index (HDI), including an explicit focus on women and girls. Since its creation in 1990 the HDI has been a central pillar of multidimensional poverty and a key instrument to measure both how much we have achieved and the challenges ahead. The report is also a timely addition to the calls made by the Commission on Global Poverty, the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development and others for incorporating quality of life dimensions into the way we understand and determine human deprivation.

I am excited by the prospect of a broader, more sophisticated approach to determining poverty. But all the best data in the world won’t do us much good if they sit on a shelf collecting dust. They must be used to influence decisionmaking and accountability, and ultimately to transform the lives of the world’s most vulnerable people. The last 15 years have shown us that progress on poverty is possible. But we also know that it is not inevitable— nor has it been universal. My hope is that this report will catalyse the global community to ensure that, this time, no one is left behind. Let’s not squander this momentum.

This text was originally published in the Human Development Report 2016 “Human Development for Everyone” .Please, see special contribution on page 57.

The HDialogue blog is a platform for debate and discussion. Posts reflect the views of respective authors in their individual capacities and not the views of UNDP/HDRO.

HDRO encourages reflections on the HDialogue contributions. The office posts comments that supports a constructive dialogue on policy options for advancing human development and are formulated respectful of other, potentially differing views. The office reserves the right to contain contributions that appear divisive.

Photo: Mrs. Florence Owens Thompson, The Migrant Mother, 1939. Courtesy Library of Congress.